The Herd Cometh – and then It Runs Away

The Trouble with Bubbles

When Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve Chair and longtime icon of the free market, testified last October before the House Oversight Committee on the current financial crisis, he did something that he had not done much very much in his 18 glorious years as the head of the Fed: say “Oops.”

The 82-year-old acknowledged that he had made a mistake in believing that the nation’s banks, operating in their own self-interest, would adequately protect their shareholders and avoid unreasonable risks in the financial markets. Such economic decision-making, made possible through lax regulation and low interest rates that Mr. Greenspan once endorsed but is now shying away from, was, as he put it, “a flaw in the model that defines how the world works.” Indeed, Mr. Greenspan’s world doesn’t seem to be making much sense as it once did.

And while Mr. Greenspan refused to take the blame for the current crisis, he also admitted he’d been wrong about one other not-so-minor phenomenon of the last decade or so: the housing boom, which began under his watch in the late 1990s. Or, to put it more precisely: Mr. Greenspan admitted that the housing boom, which had been fueled by his famously low-interest rates, had actually been a big, exuberant bubble, which now, of course, has burst and created turmoil in the nation’s financial markets and brought about a fierce recession, the consequences of which we are only now beginning to see.

In making the spectacular admission that his belief in the power of markets and rational economic decision-making had allowed him to mistake a boom for a bubble, Mr. Greenspan shed some light on the peculiar nature of financial bubbles: it’s where market behavior stops and herd-like, exuberant speculation takes over; where the true price of an asset is driven by psychology, not economic principles; where prices are expected to continue to rise and rise and rise. And when this faith in ever-increasing prices becomes shaken, well, the herd runneth away, and the bubble deflates, often with dire consequences for the larger economy.

But what drives the herd? For one, investors and buyers have imperfect – in the parlance of economists, “asymmetric” – information about markets. Second, risk-taking and risk-evaluation move in tandem; in a boom, people take more risks, and conversely, in a downturn, people take fewer risks—a recipe for disaster.

The housing bubble of the last ten years found its stride alongside another one: the stock bubble of the 1990s. Between 1996 and 1999, the prices of stocks in the Standard & Poor index rose by seven-fold, driven by people fanatical about the new dot-com technologies. This in turn drove up demand, and made prices rise. And then the herd came to feast, with each buyer expecting that the next would be willing to pay more. And so prices rose. But, seemingly just as quickly, in 2001 the stock bubble burst. At some point, the next buyers in line decided they weren’t willing to pay more – and sure enough, the rest of the herd began to run from the stocks. And, just like that, boom became bust.

Rather than curtailing it, the dramatic collapse of the high-tech stock bubble in the late 1990s fed the housing boom even further. As newly cautious investors sought more secure investments, they turned to housing. Builders worked feverishly to match the supply of homes to the increasing demand, which was, to put it mildly, a losing yet profitable battle for homebuilders and mortgage lenders alike. Prices shot even higher, and expectations of home prices in the future went apace. Enter psychology: the expectation that home prices would continue to rise, perhaps indefinitely, led more Americans to buy more real estate than they otherwise would have. And so it went.

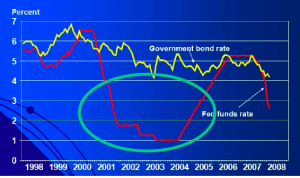

But that wasn’t all it took for the housing boom to become a bubble: it also needed cheap money and lax lending standards for mortgages. Especially after 2001, as the economy began to slow, the Fed, with Mr. Greenspan at its helm, loosened its monetary policy to hold off a recession. Lower interest rates then made mortgage rates – whether fixed or the more reckless adjusted mortgages – even cheaper.

Add to this a highly deregulated mortgage industry and increasing breezy lending standards for potential homeowners, then it became all the more easier for Americans to buy a home, even as prices continued to rise.

And to finance all of this lenders and bank concocted financial mechanisms – the now-infamous collaterized debt obligations, or bundled mortgages – which sliced and diced and sold and re-sold mortgages around the world on the erroneous belief that the risk could be effectively minimized by bundling the mortgages and securitizing them and passing them on to secondary parties. Thus, the whole thing kept its perverse energy going.

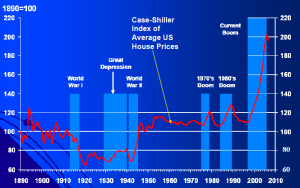

During those heady times housing prices did strange things. Having held relatively steady from the 1950s until 1995 relative to inflation, from 2002 to 2006 housing prices had risen more than 7% a year and nearly 32% overall. But starting in 2006, that all changed. As information about the true risks involved reached one person, it reached another and another – and the whole thing spread like a virus. As a result, the bubble popped, and once it did, the herd ran away just as quickly as it had come to feast. Prices started to fall – quickly – basically as quickly as they had shot up. The bubble deflated.

That the herd runs away as fast as it ran toward the bubble is part of the sorry logic of a bubble: The irrational dynamics that perpetuated the bubble – the belief that prices would only continue to rise as buyers lined up – also helped to undo it as prices began to slip as demand waned and home values began to plummet.

Experts predict by the end of 2009 that housing prices nationwide will have fallen by more than 30% – leading to a loss of more than $100,000 per homeowner and a loss of $7 trillion in housing wealth. That still excludes the foreclosures that have besieged homeowners, as they are unable to pay their mortgages, which were pegged on the expectations of rising home prices. Now, over-supply has put a glut on homes. Such is the sad cycle.

In the end, the burst of the housing bubble and the resultant shocks in the financial markets will have cost the economy trillions of dollars in wealth, left many Americans owing more on their home than it is worth, and of course has left some of the nation’s biggest and most famed financial institutions looking at their balance sheets and scratching their heads.

Now that it’s burst, economists and policy wonks are busy slinging mud. Liberal economists who had warned of the housing bubble before it burst, and who see market imperfections as something the government must protect against and be wary of, are happy to place blame on conservative policymakers and economists like Mr. Greenspan.

Greenspan had famously denied the presence of a bubble and maintained that the rise of housing prices had been basically justified by increased earnings and lower interest rates, which had drastically reduced the cost to own a home. Sure, conservatives conceded, there were some boom-dynamics at play in housing, but housing prices had never dropped in the United States to a great degree before, so why worry so much? It was really an argument over bubbles: whether they can be prevented or are just natural market occurrences. But it seems as though the events of the last 18 months have started to change some people’s ideas about the danger of bubbles.

Which brings us back to Mr. Greenspan and the terrible lesson he’s learned about bubbles: you don’t know that you’ve actually experienced a bubble until it’s too late, that is, until prices have already fallen. Unfortunately, for liberals and market conservatives alike, such disasters are only seen in the clear, unforgiving light of hindsight.

By Mark Prentice

Mark Prentice is an exchange student from Seattle at the John F. Kennedy Institute for North-American Studies at the Free University of Berlin.

2 Comments, Comment or Ping

Jon Prentice

What’s the next bubble? How do we drive the herd back the right direction? We need an economically sustainable way to fuel more of the prosperity of the last 20 years.

Feb 24th, 2009

L. Rosenberg

Good article. I would be very interested in learning if anyone is undertaking an analysis of all ‘heard mentality’ news articles, tv news coverage, investment shows (like Jim Kramer’s Mad Money), etc. that fed us with ‘asymmetric information,’ helping to inflate this bubble and the last high tech stock bubble. Surely media needs to do some self evaluation and learn from its mistakes as well. Much news ‘coverage’ is really corporate propaganda in disguise enabled by lazy journalists. ‘Let the buyer beware.’

Feb 24th, 2009

Reply to “The Herd Cometh – and then It Runs Away”

You must be logged in to post a comment.